How can the Social Sciences help unlock transformation to address the biodiversity crisis? Scholars share their thoughts

The Swedish Biodiversity Symposium held October 22-24 2025 challenged participants to reflect on how we can respond to the biodiversity crisis through the five types of transformative strategies established in the IPBES Transformative change assessment. Thanks to the organisers, every session of the Swedish Biodiversity Symposium brought together mixes of scientists, practitioners, business leaders and policymakers to discuss the what, the how and the who of transformation.

Spurring transformative policy and action is no straightforward task and requires new types of approaches and knowledge. Social sciences can help in this task by reframing the issue of biodiversity and asking powerful questions from a wide range of perspectives. Social science dimensions on biodiversity can help lay the ground for transformative change in ways that are useful for both policy and action, including through centring the topic of power and weaving diverse knowledges.

In Session 15 Advancing social science dimensions on biodiversity to spur transformative policy and action, co-organised by the University of Glasgow, Focali - SIANI, and the SLU Swedish Biodiversity Centre, seven social scientists, Aditi Bisen, Katarina Haugen, Misagh Mottaghi, Anamika Menon, Hanna Ekström Pigot, Romina Martin, and Marie Stenseke, representing a range of disciplines, shared their research. The panellists presented a wide range of interesting cases from around the world. Their combined reflections are a powerful demonstration of the ways that social science can contribute to unlocking transformation, including by addressing power and providing a basis for equitable integration of diverse knowledges, and complementing other forms of research policy and practice aimed at confronting the biodiversity crisis.

We invited the session speakers in a panel discussion to reflect on two questions that help us further understand how the social sciences can help to drive transformative change, and here we invite you to read their compelling contributions in their full depth:

1. How can the social sciences reframe the issue of biodiversity in order to ask powerful questions and engage new perspectives?

Katarina Haugen, University of Gothenburg:

“The current biodiversity challenges cannot be addressed without also addressing how humans and our societies interact with the natural environment. Also, how values, views and behaviour are translated into policy and planning priorities and approaches. It is well established that detrimental impacts of human activity have caused and continue to cause severe biodiversity loss, and therefore this is also where solutions must be sought. This in turn requires efforts from social sciences, especially together with other key (natural) disciplines, not least in cross-disciplinary research collaboration. Human geography, being the spatial social science discipline, emphasises the relationships and interaction between humans and the(ir) environment on different scales: whether in terms of urban development; population, migration, mobility and tourism; patterns of economic activity; and wellbeing in an everyday life perspective. Geographical research can contribute with in-depth understanding of place-specific prerequisites and path dependencies that underlie observable patterns, thereby enabling learning about both good and not-so-good examples, and identifying potential keys for change – which can then (hopefully) be scaled up and leveraged for broader impact.”

Aditi Bisen, Lund University:

“The social sciences can reframe the issue of biodiversity through discussions around 'value and valuation' of resources. The social sciences could help us explore biodiversity as not a fixed ecological quantity, but a socially constructed categorization which engages with multiple values - instrumental, but also intrinsic and relational. This means that there is need to acknowledge the varied valuation processes that relate to these multiple values, such as institutional, economic, or cultural valuation processes. The social sciences also provide a critical lens to understand biodiversity. Instead of looking at biodiversity as an objective variable, the social sciences help to pose how and why questions about the valuation of different lifeforms, contexts, and situated practices. This also helps to investigate how and why some of these lifeforms, contexts, or practices become 'valuable' while others are often seen as disposable or substitutable.”

Hanna Ekström Pigot, Lund University:

“Reflexivity – To reflect about one’s own practice is something that is prominent in social sciences, and something that I think biodiversity research would benefit from when aiming for supporting policy and practice. This would mean being transparent about what assumptions our methods come with, and how these assumptions affect our outcomes and policy recommendations. Based on what we’ve heard in the session, important questions to ask could be: How do we view and value other species in planning for urban ecology and nature-based solutions? What does the assumption of landowners as foremost an economic optimizer hinder us from seeing? What does an ecological model not allow us to see, and does that lead us in a certain direction when giving policy recommendations?

Power, culture, norms, justice– A common argument is that research should support evidence-based policy, and many natural scientists strive to do the best possible science in the hope that it will lead to better decisions for the environment. But there are so many aspects that have a role in decision-making, and these are aspects that social scientists are trained in analysing and explaining. A focus on power structures, culture, norms, and justice are all aspects that we need in order to understand why biodiversity policy fails, and what would be needed to address them.

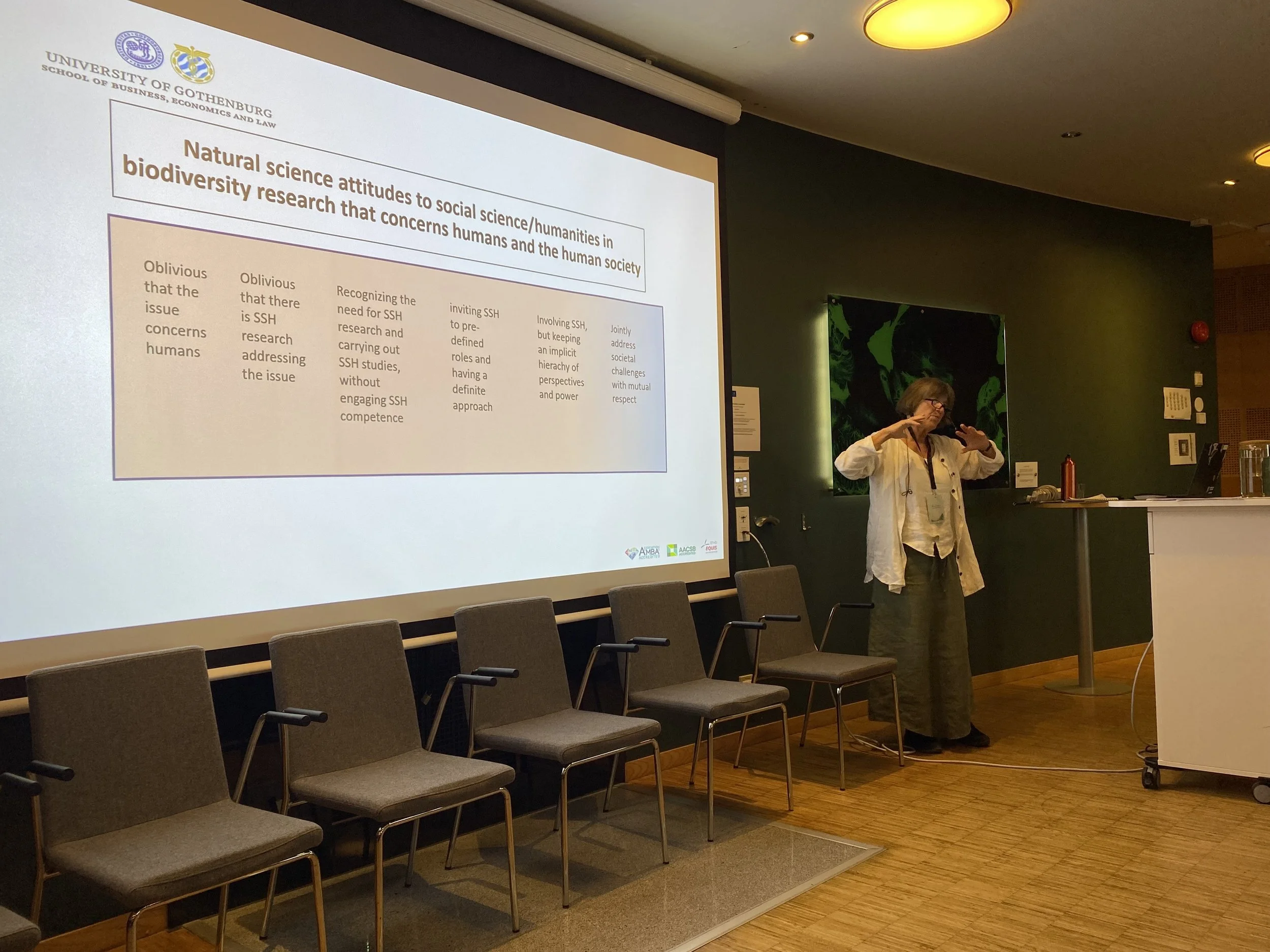

Focali members Marie Stenseke University of Gothenburg / SLU and Hanna Ekström Pigot, Lund University was among the speakers in the session in photos above in talks and final panel together with all panelists that can be viewed in the session Agenda here where all speakers and their focus in the session is included.

2. What can applying social science lenses reveal about biodiversity related problems and the societal conditions that ultimately drive biodiversity loss and impede transformative change?

Anamika Menon, Swedish Agricultural University: Applying social science lenses shows that many environmental problems including biodiversity loss, are fundamentally social problems. Instead of treating it as an issue that can be solved by removing people from landscapes, social science pushes to ask why biodiversity loss happens, who benefits from dominant conservation narratives and who bears the costs. It highlights the power dynamics, the structural inequalities and political and economic drivers that shape environmental outcomes.

An example of transformative change comes from the Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala, India. When the area was declared a tiger reserve in 1978, forest-dependent communities were relocated outside the core zone and lost their livelihoods. As a result, poaching increased not because local people wanted to extract forest resources but because they lacked alternative income opportunities. When authorities began engaging with local communities, they realised this and recruited them as forest watchers and guides, roles for which they were uniquely skilled.

By addressing local needs, conservation became more effective which reduced poaching and helped in shared stewardship of the forest. This case shows that protected areas and community-managed areas need not be on opposite ends. They can be complementary when governance is inclusive and attentive to social realities.

Social science perspectives help uncover such root causes of biodiversity loss, including entrenched interests that may resist transformative change and dominant development narratives that normalise extractive economies. They also bring to attention the diverse ways people value, use, and sustain biodiversity.

Tiger in Tiger reserve in Ranthambore national park India by Sourabh Bharti via Canva.

Misagh Mottaghi, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Applying social science perspectives helps to better understand that biodiversity loss is not just an ecological issue, it is also deeply social and political. These perspectives help uncover how our current governance and planning systems, along with established cultural norms, often create a divide between humans and non-human species, prioritizing human interests while marginalizing other forms of life. By understanding the roots of this separation, social science can help reframe biodiversity as part of an interconnected system, emphasizing that its resilience is essential for sustaining all life. These perspectives can also highlight the often-hidden tensions that arise when considering nature and humans within a predominantly hierarchical decision-making framework. Social science approaches can bring to light the power dynamics, institutional biases, and predominant narratives that determine whose values are prioritized. They can redefine biodiversity as a shared concern and a matter of shared responsibility. In short, social science plays a crucial role in developing more equitable, socio-ecologically grounded approaches that align human systems with the long-term resilience of the broader living world.

Focali member Anamika Menon PhD student at SLU (in photo above) was one of the panelists together with all session speakers available in the session program here.

The session was co-organized by:

Stephen Woroniecki Focali member at University of Glasgow together with Tuija Hilding-Rydevik and Johanna Tangnäs, SLU Swedish Biodiversity Centre and Maria Ölund Focali, Wexsus at University of Gothenburg.

Related

Read the session invitation text and program here: “Advancing social science dimensions on biodiversity to spur transformative policy and action”

In addition to the panellists above Marie Stenseke gave a “framing talk on the imbalanced structures in biodiversity research and how to handle them”. The session talks was not recorded but a related talk by Marie Steneske on “how to enhance integration of knowledges between disciplines and other knowledge holders, to include social dimensions and bridge the knowledge-to-action gap” was recorded at the Focali annual meeting and is available in this Focali You Tube playlist.

Focali member Stephen Woroniecki, University of Glasgow, co-led the planning of this session and has initiated the new Focali work stream “The role of Social Dimensions of Biodiversity – in Research, Policy and Practice” read more about its focus and past related dialogues here. Connect with Stephen if you would like to discuss future collaboration ideas related to the focus of the session or work stream.

The promotion card for the session used in social media ahead of the symposium and as backdrop during the session.